The AI Investment Decision: How CFOs Are Balancing Growth and Margin Risk

Sections

TLDR

- AI costs behave differently. Per-user exposure is uncapped and familiar cost levers don't apply.

- AI already consumes 22% of cloud spend at growth-stage companies, years ahead of most forecasts.

- Margin erosion tracks with governance gaps, not AI spend. Full governance dramatically lowers risk.

- 72% of CFOs don't greenlight AI investments outright. They pilot, require offsets, or defer.

- The CFOs who greenlight AI confidently aren't less cautious. They've built better systems.

Your head of product proposes an AI feature. The math looks favorable: 4–5% revenue lift against 2–4% cloud cost increase. Positive unit economics on paper.

Yet 72% of CFOs don't greenlight it outright. They pilot first, require offsets, or defer entirely.

This hesitation reflects something more nuanced than risk aversion. AI costs behave differently than traditional infrastructure. The forecasting tools Finance relies on weren't built for this cost profile. And the CFOs who navigate AI investment successfully are not set apart by their appetite for risk. They are set apart by the operational infrastructure that supports their decisions.

This article examines what separates organizations that absorb AI acceleration without margin erosion from those that don't, and provides a decision framework for funding AI initiatives responsibly.

This analysis draws on Cloud Capital's Q4 2025 CFO Survey of 100 senior finance leaders at growth-stage technology companies (50–1,000 employees, US and UK). All margin and forecast references reflect the 12 months preceding the October 2025 survey. "AI-heavy" denotes organizations where AI/ML represents more than 20% of total cloud spend. For full methodology, see The Cost of Compute 2026.

AI Costs Arrived Faster Than Planned

AI workloads already consume 22% of cloud spend for growth-stage technology companies. That level of exposure typically builds over several planning cycles. Instead, it arrived all at once.

The speed matters because AI costs introduce patterns that differ fundamentally from traditional SaaS infrastructure.

Why AI costs resist traditional forecasting

Traditional SaaS infrastructure scales predictably. More customers, more compute, foreseeable cost curve. AI workloads don't follow this pattern.

Consider what this looks like in practice: A single customer using an AI-powered feature aggressively can generate more compute cost in a month than thousands of typical users. An AI feature that averages $0.15 per user suddenly costs $12 for a power user who treats it as their primary workflow. Multiply that across a segment of engaged customers and unit economics shift mid-quarter with no warning. Traditional infrastructure had natural ceilings on per-user cost exposure. Foundation model inference doesn't.

The underlying dynamics explain why:

- Per-user cost exposure is effectively uncapped. Traditional infrastructure costs scaled with aggregate usage, and individual users had modest impact on the total. AI inference costs scale with how intensively each user engages with AI features. A small cohort of heavy users can materially shift margins.

- On-demand pricing doesn't respond to familiar levers. Most foundation model APIs lack the commitment structures (Reserved Instances, Savings Plans) that give Finance predictability on traditional cloud spend. Volume discounts exist but don't provide the same cost certainty. The toolbox Finance uses elsewhere doesn't apply.

- Inference costs depend on user patterns Finance cannot see in real time. Unlike traditional infrastructure where usage correlates with known metrics, AI inference costs shift with how users interact with features. Visibility comes after the bill arrives.

- Training and experimentation add episodic spikes. For organizations fine-tuning models or running experiments, training runs can consume more compute in a week than steady-state operations use in a month. A single training run might cost $75k against a $40k/month baseline. These spikes follow engineering milestones, not financial planning cycles.

These dynamics break the linear forecasting assumptions Finance relies on elsewhere. Which is why operational controls matter more, not less.

Same AI Investment, Different Margin Outcomes

Organizations where AI represents more than 20% of cloud spend (n=47) are 2.6× more likely to report gross margin decline over the past 12 months than those with moderate AI exposure (5–20%, n=43).

That gap demands explanation. What separates the organizations absorbing AI costs from those experiencing margin erosion?

What separates the risk cohort

The organizations reporting gross margin decline share two characteristics:

- Governance gaps. Only 14% have full governance (enforced budget caps, approval gates, and tagging/alerting that actually fire in production) compared to 75% of AI-heavy organizations with stable or improving margins.

- Infrequent forecasting. Only 14% forecast monthly, compared to 31% of the success cohort.

The differentiating variable is operational infrastructure. Governance and forecasting cadence predict margin outcomes more reliably than AI spend levels.

Why Guardrails Alone Don't Protect Margins

72% of CFOs apply financial guardrails to AI investment decisions.

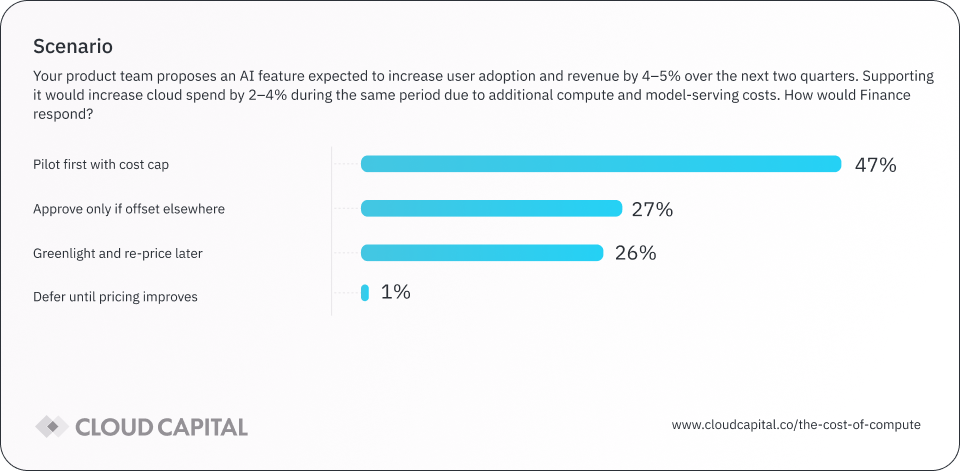

We asked CFOs how they'd respond to their head of product proposing an AI feature with positive unit economics on paper (4–5% revenue lift, 2–4% cost increase). Their responses:

- 47% pilot first with cost cap and review period

- 27% approve only if offset elsewhere

- 26% greenlight and re-price later

- 1% defer until pricing improves

CFOs are not blocking AI investments. They are putting financial guardrails in place early, before cost volatility forces reactive intervention. The instinct is correct. Guardrails provide decision control. But guardrails alone haven't eliminated margin pressure for the organizations experiencing it.

The interaction effect

Among AI-heavy organizations, the behavioral response (greenlight vs. pilot) matters far less than the operational infrastructure underneath it.

Source: The Cost of Compute 2026, Cloud Capital Q4 2025 CFO Survey

In other words, similar decision behavior leads to very different outcomes depending on whether governance is in place. Organizations with full governance can greenlight AI investments and absorb the cost dynamics. Organizations without it experience gross margin erosion even when they apply caution.

The guardrail buys time. Governance determines whether that time gets used productively.

The implication: Guardrails let you say "no" or "slow down." Operational systems let you say "yes" with confidence.

Governance Is the Differentiator

Among AI-heavy organizations, 3% of respondents with full governance reported gross margin decline (n=37). Among those with partial or no governance, 33% of respondents reported decline (n=18). That's an 11× difference in margin risk.

Full governance means enforced controls. Not planned. Not partial. Specifically:

- Budget caps enforced below company level (by team, product, or workload)

- Approval gates enforced for new resource provisioning

- Tagging policies enforced at provisioning, not retroactively

- Alerting tied to forecasts, not just absolute thresholds

Monthly cadence compounds the advantage

Monthly discipline catches deviations early, enabling mid-quarter corrections that quarterly cycles miss. Among AI-heavy organizations, quarterly forecasters were 2.5x more likely to report margin declines than those who forecast monthly.

Organizations with full governance, excellent visibility, and monthly cadence are overwhelmingly represented among those absorbing AI acceleration without margin erosion. Only 11.5% of surveyed organizations have implemented all three.

The board and investor lens

This is a valuation issue.

As Todd Gardner, managing director at SaaSonomics who has funded over 100 SaaS companies, wrote in a recent analysis of Cloud Capital's survey data: a 5-point gross margin decline can translate to a 25% valuation decrease at constant multiples. The math is punishing because "COGS matter more to investors than operating expenses... high-gross-margin companies are worth more" given that cloud costs are harder to cut without immediate consequences.

Gardner's takeaway for CFOs making AI bets: you might be able to explain away gross margin decline, "but only if you can back it up with data isolating core gross margins from development costs." That's exactly what governance infrastructure provides. The ability to show the board that AI investment is driving margin expansion, not erosion.

The 11× difference in margin risk between governed and ungoverned organizations is the kind of operational signal that shows up in growth equity and late-stage diligence.

For the full valuation analysis, see Todd Gardner's SaaS Gross Margins Are Under Pressure (And It's Bad News for Valuations).

The Decision Framework

Before greenlighting AI investments, confirm three things:

1. Governance is fully implemented, not ‘in progress.’ Budget caps, approval workflows, and tagging policies are enforced today, rather than left as future plans.

2. Forecasting cadence is monthly. Quarterly cycles allow variance to compound undetected. Monthly discipline catches cost deviations while they're still correctable.

3. COGS confidence is high. If Finance isn't confident in cloud COGS accuracy today, adding AI workloads will amplify the problem. Check out Mapping Cloud Spend to COGS and OPEX for cloud cost allocation and accounting guidance.

If you're not there yet

Most organizations aren't. Here's a 2–3 quarter path from partial to full governance:

- This month: Enforce tagging on all new resources. You can't govern what you can't see.

- This quarter: Implement budget caps at the team or workload level. Not just company-wide. Begin forecasting monthly with Engineering.

- Next quarter: Tie alerting to forecast thresholds, not just absolute spend limits.

Each step independently reduces margin risk. Combined, they build the infrastructure that lets you greenlight AI investments with confidence.

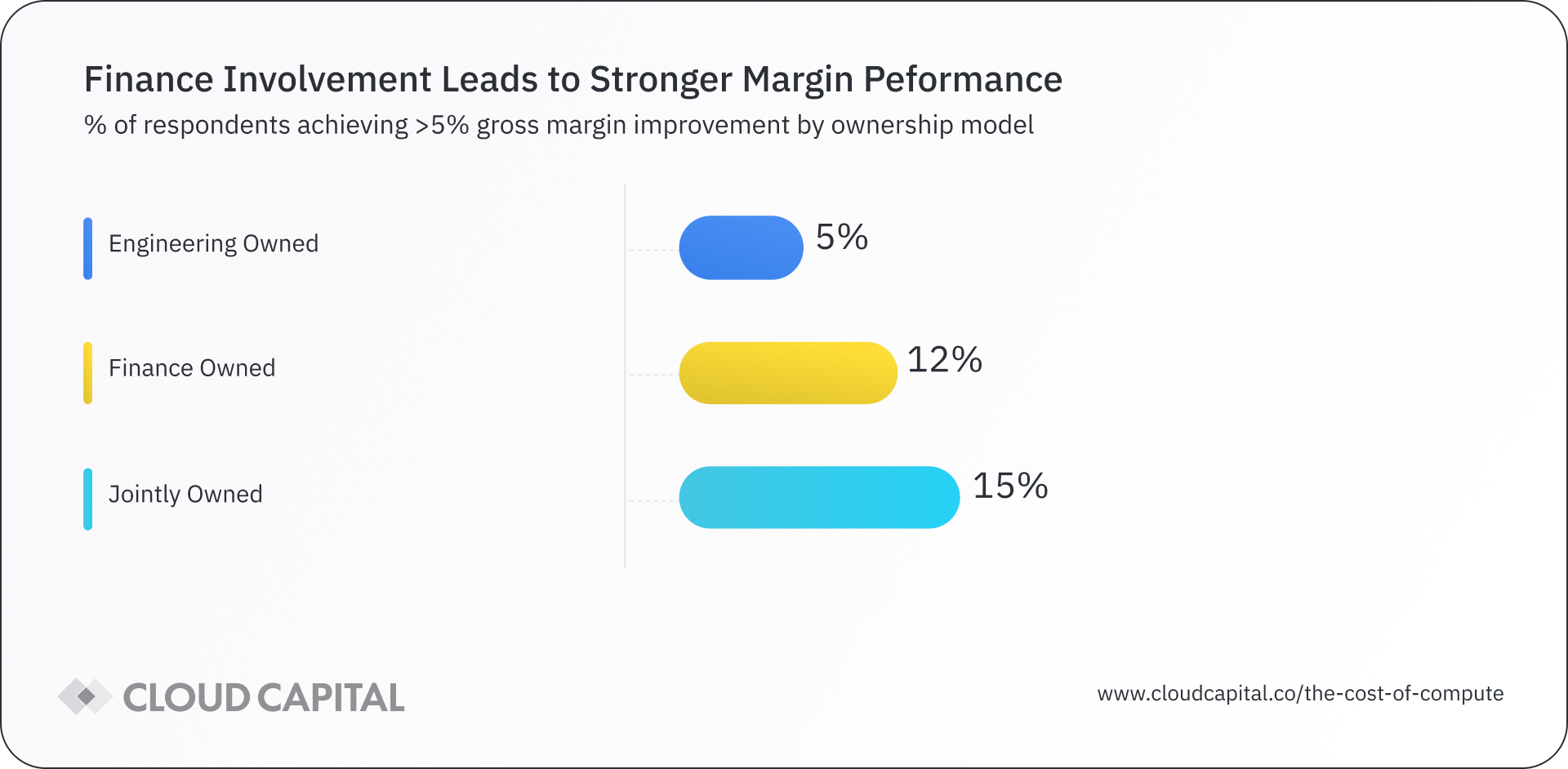

The operating model that works

Joint Finance-Engineering ownership outperforms every other model in our data.

Finance sets the spending envelope and owns variance explanations. Engineering operates within that envelope and provides technical context. When spend exceeds forecast, Finance defines the financial constraint; Engineering identifies the operational levers.

It's about Finance applying the same accountability to cloud infrastructure spend that it applies to payroll: clear budget authority, regular forecasting discipline, and responsibility for explaining variances.

The Path Forward

CFOs who can greenlight AI investments without margin erosion don’t stand out for being more aggressive or more conservative than their peers. They stand out because they have built operational infrastructure that makes AI costs forecastable.

73% of CFOs expect cloud's share of revenue to increase next year. AI's share of cloud infrastructure costs will grow with it. The organizations that build predictable systems now will absorb that growth. The organizations that rely on guardrails alone will continue managing variance after it's already hit margins.

Predictability is the competitive advantage. The question is whether you're building it.

FAQ